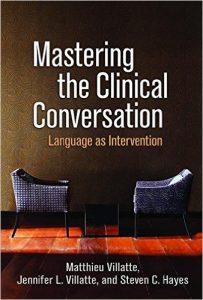

“Mastering the Clinical Conversation: Language as Intervention” was published in late 2015 by Guilford Press. The book’s authors, Matt Villatte, Jennifer Villatte, and Steven Hayes, have produced, in my opinion, the first clinical Relational Frame Theory (RFT) manual that is both immediately useful to clinicians, and repays with deeper study and repeated readings. The manual will be of interest to researchers and clinicians concerned with the empirical development of psychotherapies, and therapists seeking to understand how therapeutic interactions can be enhanced by using contemporary behavioural principles. [For the remainder of this review I will use the abbreviation “MtCC” to refer to the book.]

“Mastering the Clinical Conversation: Language as Intervention” was published in late 2015 by Guilford Press. The book’s authors, Matt Villatte, Jennifer Villatte, and Steven Hayes, have produced, in my opinion, the first clinical Relational Frame Theory (RFT) manual that is both immediately useful to clinicians, and repays with deeper study and repeated readings. The manual will be of interest to researchers and clinicians concerned with the empirical development of psychotherapies, and therapists seeking to understand how therapeutic interactions can be enhanced by using contemporary behavioural principles. [For the remainder of this review I will use the abbreviation “MtCC” to refer to the book.]

MtCC presents a wholly functionally-analytic approach to psychotherapy, based on a basic science account of language and cognition. The book’s integrative presentation means that the principles described are relevant to the practice of various psychotherapies, including cognitive-behavioural, systemic, humanistic and psychodynamic approaches (more on this later).

Background

MtCC was a hotly-anticipated title within the contextual behavioural science community, partly as there was the promise of a clinically-oriented RFT handbook, that was not an “ACT book”, and also because of the word-of-mouth buzz generated by the training workshops that Matt and Jenn Villatte had been giving over the previous 3 years.

These workshops, presenting what could be done with clinical RFT, demonstrated that interventions may be developed directly from using relational framing principles. All without requiring a model like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, or using middle-level terms.

I was fortunate enough to participate in a workshop Matt led in London in 2013, hosted by the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies. This workshop was well-attended by a diverse audience of clinicians and academics (along with ACT aficionados, there were participants across theoretical orientations, from cognitive therapists, solution-focused and systemic therapists, behaviour therapists, to humanistic and psychodynamic therapists: it felt quite unusual to have such an eclectic crowd for an event hosted by a CBT organisation).

The workshop was excellent. Over two days Matt demonstrated how RFT could provide from the ground up a way of conceptualising problems functionally and working with clients with greater precision in therapeutic language, using various types of relational framing. This was beyond the usual work presented to clinicians about RFT’s relevance, such as in the development of apt metaphors… this was seeing the therapeutic context wholly through a RFT lens.

What was equally impressive was the integrative nature of the training: while behavioural in focus, there were links made across a range of psychotherapies regarding the use of language to achieve therapeutic aims. It could be observed, in fact, that there was very little over the 2 days that was “ACT” at all: it was much more about understanding (in RFT terms) practices in mainstream, established approaches or speaking about the generic tasks and goals of therapy.

So, my hopes were high that MtCC may reflect my workshop experience of clinical RFT.

“Accessible RFT”

Since the 2001 publication of original RFT book (dubbed “Purple Hayes” due to the cover design, and possibly also for the experience that the text has on the reader(!): an infamously dense and complex manuscript), there has been a pressing need for readable texts to introduce RFT to non-academics. Two preceding texts, “Learning RFT” and “The ABCs of Human Behavior”, have been excellent efforts at tackling this, particularly by describing the effects of rule-governed behaviour and then presenting the properties and implications of relational framing.

MtCC presents a further refinement. It is an accessible introduction to RFT, oriented to clinical situations. MtCC stands on the shoulders of the RFT books that preceded it, capably presenting relational learning in a digestible way for the general reader. It helps that the principles described in the first few chapters, are then expanded upon throughout the remaining ones, meaning that the reader has plenty of clinical examples to become fluent in the functional way that MtCC describes psychotherapy.

The initial chapters describe the basic principles of how language evolved as a unique form of learning, and the ways that it can lead to problems and challenges (along with advantages).

The authors present their definition of language – “the learned behavior of building and responding to symbolic relations” – and unpack this to help the reader understand the book’s stance.

First, language is about relating. It is a skill that applies beyond words, to any way that symbols can be related. And, at least for humans, this skill includes relating in ways based on social whim (rather than just to the inherent properties of the object being related). The authors argue this makes it possible for ”everything to mean anything”.

Second, language is learned: the authors discuss how it is the only learning process that is itself learned, and that once learned it alters all other forms of learning. Due to the ubiquity of symbolic relating, therapists are working with language, even when they use methods such as inducing silence, mindfulness, hypnosis or imagery. The authors make the case that knowing the behavioural principles suggested by RFT may help clinicians to work with a broad range of clinical problems in a coherent and efficient way, regardless of their clinical tradition.

“The conversations that happen in psychotherapy and other clinical interactions are, in part, a process of learning how to manage relational frames and the contextual cues that regulate them in the service of living well”

The third chapter is key, presenting a framework for using language in therapy and considering the tools (relational frames) that can be used clinically. The chapter orientates the reader to how change may occur: therapists work to alter the client’s symbolic context in various ways. Rather than attempting to remove experiences, the therapist is encouraging the client to be more sensitive to the useful aspects of their experiences, in order to broadening and build behavioural repertoires.

The authors describe overarching goals (promoting flexible sensitivity to context, and functional coherence) and a strategy (altering contexts, so that transformation of symbolic functions occurs). Helping clients to be more in contact with their experience in a broader way may enable more effective behaviours to be chosen (flexible sensitivity to context). Doing so from a stance of wholeness and effectiveness (functional coherence), may allow the client’s experiences to be integrated flexibly and their actions to be in the service of meaningful living. This chapter is a fundamental statement of the focus of therapy and sets the scene for the remainder of the book.

“Without sensitivity to variations in the context, a single observation turns into a rule, a thought into a belief, a memory into a story, an emotion into a mood, and a behavior into a habit”

The fourth chapter outlines how to use RFT principles in the assessment of psychological problems. A central idea is to conduct the assessment from the client’s perspective, to support their ability to observe their own behaviours and how they are influenced (so repertoires are already being broadened in the assessment phase!). This is a necessarily collaborative process, that may involve the use of metaphors and perspective taking to connect what is happening outside of therapy, with what is happening in the therapeutic relationship. The way assessment is described in this chapter is as an augmentation of what would be done within the therapist’s theoretical orientation. The reader is encouraged to consider how they would assess context sensitivity and coherence alongside the processes important to their model.

The remainder of the book then has chapters that describe clinical methods for:

- activating and shaping behaviour change,

- building a flexible sense of self,

- fostering meaning and motivation,

- creating powerful experiential metaphors, and

- strengthening the therapeutic relationship.

Each clinical methods chapter has a similar structure: introducing the general approach, which is then divided into various component skills. For each component skill there is an outline of the therapeutic goal, why it is important from a RFT perspective, how it links with various clinical traditions, and how to do it (with example therapeutic exchanges). Several component skills are discussed in this way, before the chapter concludes with a clinical example, with an extended vignette and description of the intended functions that the therapist is trying to develop. Each chapter ends with a summary of the principles to remember for the particular skill (this content is also listed at the very end of the book, in the “Quick guide to using RFT in psychotherapy”).

The clinical examples presented illustrate the principles well. More so, they have a quality of verisimilitude: they do sound like the types of conversations heard in the therapy room. In my experience, this is unusual in therapy manuals, many times example therapeutic conversations can read as a little too contrived. The authors notes on what the therapist intends with a particular response are instructive and reinforce the chapter points.

Criticisms

As strong as MtCC is, it is not to say that the text cannot be criticised. For one, I have heard a view that publishing this book is premature: there is still a lot more experimental RFT research required before reliable statements can be made about certain types of relational framing. I see this as a tension between the (necessary) goal of doing basic science, and presenting the implications of this research for applied settings.

What may surprise the casual reader is the amount of RFT research that has been done over the last 15 years. The authors do a great job in describing how this research has implications for psychotherapy in general, rather than just for contextual approaches like ACT. Like any empirically-based approach, there are likely to components presented in MtCC that will be revised and refined with further research. Producing a treatment manual at this point, to outline RFT’s usefulness to the clinician, seems an important goal in its own right.

A second criticism I have heard is that the book is not “functional enough”, and that what is being presented is a form of “topographical RFT”. It is accurate that the approach described in the text does not involve doing a “true” functional analysis – controlled experimentation of the manipulable aspects of the client’s environment – however, there are a variety of conceptual and practical reasons which functional analysis is not done in this way in clinical practice (Haynes & O’Brien, 1990; Hayes & Follette, 1992, 1993). In many psychotherapy settings it is not possible to spend extended periods engaged in this form of experimental analysis: amongst other reasons, few clients will have the patience for such an enterprise.

I think in MtCC the authors have struck the right balance, presenting assessment of sensitivity to context and coherence as additional facets of what the therapist would be doing when developing a formulation. There are certainly a number of methods and ideas discussed in Chapter 4 about how to do assessment, even if it cannot be said (yet) that functional analysis using RFT is definitively described. I have no doubt that in the coming years there will be other clinical RFT books published, from different authors, with other approaches to assessment and conceptualisation. It is the early days of clinical RFT.

Resources and Strengths

This book is supported by a wealth of online materials. The reader can expand their learning by exploring the website devoted to the book (https://languageasintervention.com/), where there are many video resources that illustrate the principles, along with demonstrations of the therapeutic methods. There is also an active Facebook group to support learning.

A strength this book has is the authors’ efforts at integration, across various therapeutic models. This integration is not “anything goes” eclecticism, but rather one of considering functionally the processes of various psychotherapeutic methods. More than any other contextual text, there is a deliberate move of building bridges.

An example here is the intelligent discussion of behavioural experiments, cognitive reappraisal, and exposure, within a RFT frame (yep, pun intended). It is an interesting empirical question: when is it useful clinically to expand relational networks (such as with reappraisal or behavioural experiments) as a primary focus (compared to, say, undermining them experientially)? One hopes that the book’s impact is that it encourages RFT-informed clinical research that moves the field beyond therapy “brands” (e.g. ACT, CBT, and the rest of the alphabet soup), and generates useful principles that benefit all.

Conclusions

In my view, MtCC is a milestone work in contextual behavioural science and clinical behaviour analysis. I think it stands alongside the original guide to Functional Analytic Psychotherapy (FAP; a foundational text), in providing a behaviour analytic understanding of psychotherapy. Similar to the FAP text, the principles described could be used to augment existing therapeutic approaches. In contrast to the FAP text, MtCC presents a post-Skinnerian approach to psychotherapy, illustrating how understanding the principles of reinforcement are important within the context of the transforming qualities of relational responding.

Time will tell about the impact of this book. My hope is that MtCC becomes one of the foundational texts that new and training clinicians read, as it provides such a pragmatic framework for understanding clinical interactions. I would put this book in the same company as texts like “Motivational Interviewing”, in providing therapists with a solid footing in their sessions. Similarly I would recommend this book to experienced therapists: there’s a wealth of ideas to explore and wrestle with here. This book may just transform your approach to clinical conversations.