Exposure is one of the most powerful and effective methods therapists have to help clients whose lives are restricted by struggles with fear and anxiety. It is a classic method of behaviour therapy, with over 40 years of research to support its use.

Whatever approach to working with cognitions and inner experiences a cognitive-behavioural therapist takes in helping clients with anxiety, (a cognitive approach, such as Beckian CBT; or contextual one, like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy), there will usually be the use of exposure.

While it would seem that we should know how exposure works, recent research suggests that there is a still a lot more to discover about the best ways to engage clients in this approach.

Does habituation matter?

Many therapists have been trained in using exposure based upon a habituation rationale. Typically, sessions are conducted where the client is asked to rate their distress (using a SUDS – subjective units of distress scale) while doing exposure over the course of the session, with the aim of having distress reduce by the session end (typical treatment protocols suggest at least a 50% reduction in distress, e.g. Foa et al., 2012). What is also tracked are reductions in distress between sessions. The process of exposure is thought to be successfully occurring if these reductions in distress (habituation) are happening.

However, there is not much support for habituation being the process of change in exposure. For example, it has been found that:

1) people don’t have to experience distress reduction in session for exposure to be effective (e.g., Baker et al., 2010)

2) people don’t have to experience distress reduction between sessions for exposure to be effective (e.g., Prenoveau, Craske et al., 2013)

[See Craske et al., 2014 for a discussion of this research]

If reductions in distress in exposure sessions seems unimportant to outcome, then what should the therapist focus on instead?

Learning from new models of exposure

The contemporary empirical literature gives some indications, from an inhibitory learning perspective, and the psychological flexibility model (based on Relational Frame Theory, which underpins ACT).

The inhibitory learning model hypothesises that fear learning is not extinguished when people participate in exposure. Instead, what happens is that people learn new associations with what they fear, and this new learning inhibits old learning (such as fearful responding). From this model, the aim of exposure therapy is to maximise the ways that this new learning occurs. This could be done by:

1) violating the client’s expectancies of what will happen when doing exposure (I.e., learning is focused on whether the expected negative outcome occurred or not, or was as ‘bad’ as expected), and the degree of “surprise” a client has about the exposure practice. In this model new learning is impactful by the degree of a mismatch between what the client expects, and what they experience; sessions focus on this goal, rather than distress reduction;

2) increasing uncertainty associated with learning, by occasional reinforced extinction (the client experiencing occasional negative outcomes, such as social rejection if socially phobic, through “shame attack” exercises or deliberately doing things that will invite criticism from others), which may strengthen inhibitory learning if the client is later in contexts that would risk a relapse of fearful responding;

3) removing safety signals and safety behaviours, as these interfere with new learning. The therapist paying attention to the development of any new safety signals, such as the client learning that distress reduction reliably occurs during exposure;

4) the use of variable exposure, where exposure is conducted to items from the hierarchy in random order, without regard to distress levels or distress reduction (usually starting with the least anxiety producing item to avoid drop-out), and for variable lengths of time (again, with client agreement);

5) deepened exposure, where multiple cues are combined (that have previously been used in isolation in exposure sessions), such as the use of in-vivo (e.g., contamination with an “unclean” environment) and imaginal exposure (e.g., imagining someone becoming sick due to the contact with the client’s contaminated hands) together in an exposure session.

6) conducting exposures in multiple contexts – being creative about the range of occasions where exposure can be done, such as when alone, in unfamiliar places, or at varying times of day or varying days of the week. This reduces the risk of new learning being “context bound” (risking increased chance of relapse), such as if exposures were only done in the therapist’s clinic.

7) broadening contact by engaging in affect labelling, with the therapist asking the client to state their emotional responses, without attempting to change these responses, in the midst of exposure.

The psychological flexibility model emphasises helping the client learn how to pursue a values-based living regardless of anxiety, fear and urges (such as escaping or avoiding). For this model, the focus is on maximising client actions that are personally meaningful, whether in the presence of life-narrowing stimuli or not. The functions of anxiety and fear are transformed by experiencing them in the context of values, so that these experiences are responded to with qualities of openness, curiosity and compassion. The connection to values can mean that the client is reinforced for being in contact with fear and anxiety, in the context of acting in personally meaningful ways:

1) Engaging in exposure is explicitly linked to the client’s values, with meaningful (values-linked) activities chosen for the exposure sessions. Thus, there is a clear relationship with the stimuli and tasks chosen for exposure, and the kind of life that the client wants to be living;

2) Exposure sessions reflect the ACT approach: instead of monitoring ratings of distress levels during exposure (SUDS), the client is asked to provide ratings of their willingness to experience anxiety and other inner experiences (urges, unwanted thoughts, feelings) throughout exposure tasks. Over exposure sessions, work is done to increase willingness (through using exercises linked to acceptance, defusion, present moment contact, and flexible perspective-taking);

3) it does not matter whether the exposure task is easy or difficult (in a level of distress sense); rather, it is about how open and accepting the client is to what shows up while doing exposure;

4) exposure provides an excellent opportunity to practice experientially, the skills of psychological flexibility that ACT promotes;

5) following a session, the client should be encouraged to reflect on being willing and open during exposure, to strengthen experiential learning; if a client is starting to respond in a rule-bound way to doing exposure (“e.g., I just need to allow that feeling to be there and not fight it”), then the therapist should encourage curiosity, in light of workability (Therapist: “how has it worked in terms of your goals? How has this worked compared to other things you do?”)

Implications

Considering the recommendations from both these models of exposure, you can see that we are long way from the traditional, habituation-based approach. While the models have theoretical differences (see Arch & Abramowitz, 2015 for a discussion), there are commonalities.

For the ACT therapist, I think this can inform how to engage clients in exposure that maximises learning and flexibility, by:

- having a focus on willingness and noticing the experience of fear and anxiety, without working to reduce distress within or across sessions.

- linking exposure with “ultimate outcomes”, by engaging the client in approaching exposure within the hierarchical framing of values;

- strengthening therapist and client willingness for exposure sessions to have variability in the intensity of distress, without controlling or avoiding this (and having sessions where distress may vary, including times when it remains high at the end of the session);

- promoting present-moment awareness and expanded contact by affect labelling during exposures

- working with the client to be in contact with feared outcomes (in-vivo, imaginal) as part of openness to experience and discovery.

- encouraging client curiosity about what they are learning during exposure, without focusing on there being a “right” or “definitive” view to take;

- moving away from using hierarchies as means of structuring of exposure, and introduce more variability into exposure sessions in terms of exposure difficulty (while ensuring that the client is choosing to engage in exposure)

- expanding the contexts where exposure is practiced, so that new learning is not context-bound.

It is an interesting time to be practicing exposure therapy, with increased empirical interest in the processes that strengthen learning, and discovery of new ways to conduct sessions that may increase therapy effectiveness. These new ways to do exposure increase the options for the therapist and client to work in flexible and creative manner.

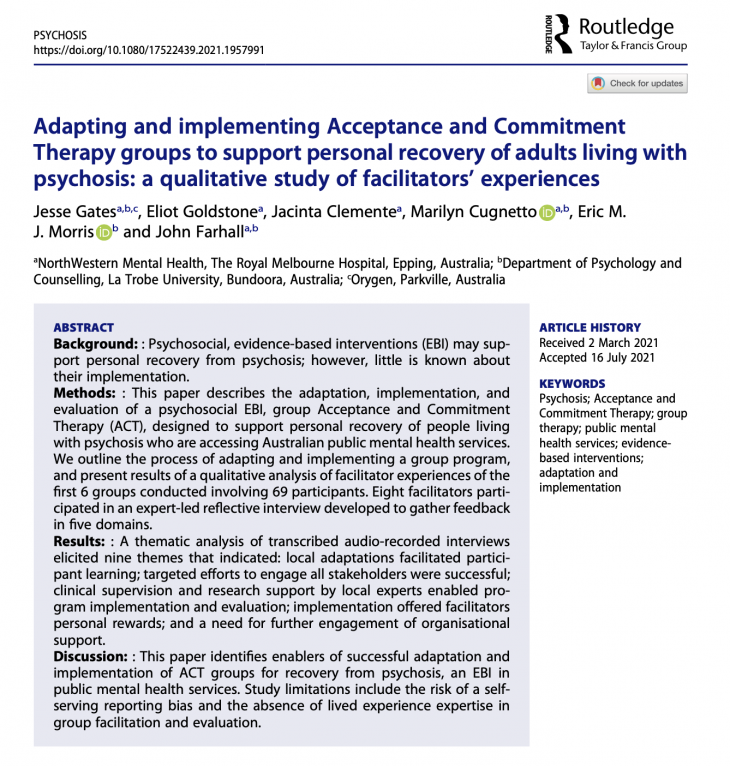

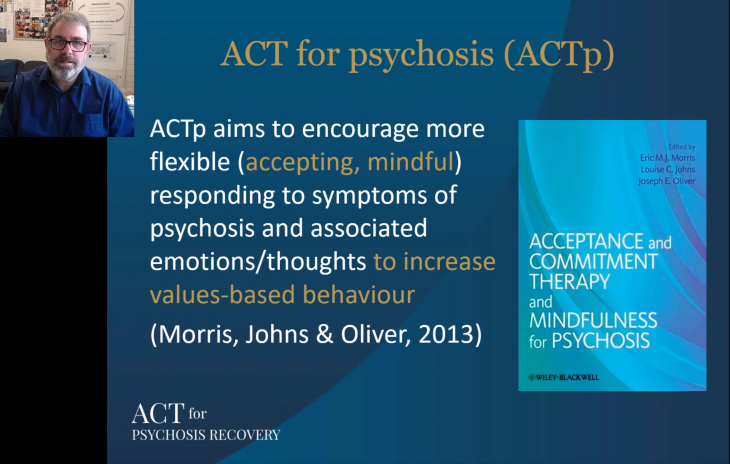

ACT for Psychosis is also described in a chapter I wrote for a new book,

ACT for Psychosis is also described in a chapter I wrote for a new book,